- Stretch

- Posts

- Reframing Stress, Balance for Learning, and Practice

Reframing Stress, Balance for Learning, and Practice

🤸♀️ Stretch 19

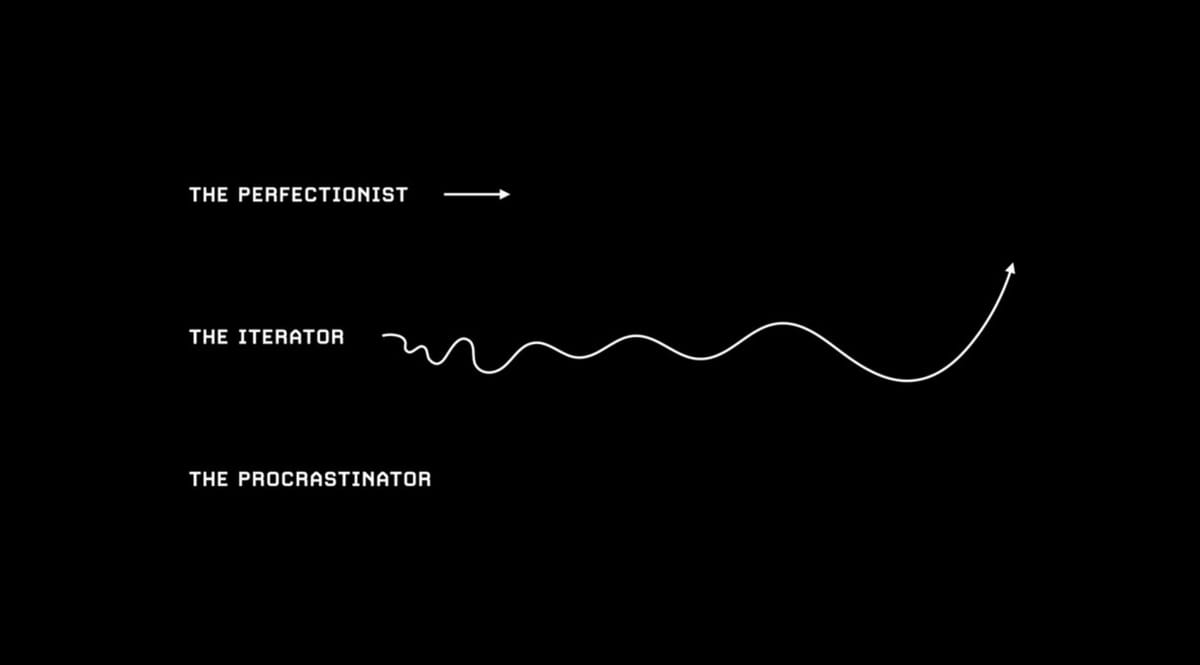

My Year of Creative Experiments isn't going so well.

I guess that means it’s going perfectly?

Because here's the thing:

As long as I'm 'experimenting' - I can't fail!

In August, I promised myself I'd come up with something during the holidays, which of course didn't happen (Lesson learned: plan ahead of time for the summer months).

In September, I was meant to do my very first podcast interview. We've had to postpone it a couple of times so now it's scheduled for October (Lesson learned: only pick experiments where I control the timing). I am super excited about this Experiment because this is exactly why I started this whole thing: out of my comfort zone + high potential for embarrassment. Perfect.

Same for this month's Experiment. It's scary. It's cringe. My mind has been doing everything in its power to talk myself out of it.

TikTok videos. I know... I want to practice speaking on camera so creating videos is an obvious way to do that (there will be no dancing!). And right now, TikTok is the best place for short-form videos. I can feel I'm resisting the platform because I don't know it - and that's the kind of fixed mindset I want to challenge.

Per Naval Ravikant's quote that has stuck with me ever since I read it:

"The people who have the ability to fail in public under their own names actually gain a lot of power."

Keep you posted! 🙈

🤸♀️ IN THIS WEEK'S STRETCH:

Reframe Stress as a Source Of Energy. Stress is not the enemy.

Balance. And how to use it to access optimal neuroplasticity.

Practice slowly. And 4 other principles from a world-class musician.

⚡️ REFRAME STRESS AS A SOURCE OF ENERGY

I’ve always admired people who are able to stay calm in stressful situations.

I used to think that meant these people don’t experience stress as I do. My pounding heart and sweaty palms — I saw these as signs of weakness.

Huberman Lab and books like The Leading Brain have helped me completely reframe stress.

Stress, at its core, is a survival mechanism.

It's my body getting ready for action, designed to focus me.

To appreciate the beauty of this stress reaction, I've found it helpful to have a basic understanding of how it works inside my body.

In my latest post, I cover:

Why stress is not the enemy

The 2 channels of our autonomic nervous system: the parasympathetic (rest-and-digest) and sympathetic (fight-or-flight)

The Physiological Sign: a hardwired technique to activate the parasympathetic nervous system when the acute stress response hits (it’s not quite as straightforward as the flick of a switch but it’s close!).

🏄♂️ USING BALANCE TO LEARN FASTER

I spent a couple of nights on a sailboat over the summer, and for at least 8 weeks after the trip, I kept feeling dizzy whenever I'd get up or move my head too quickly.

Not ideal, BUT - it sent me down a Google rabbit hole and taught me something cool about my body.

Just like our eyes have multiple functions, our ears have 2 main responsibilities:

An obvious one: hearing

A not-so-obvious-one: balance

Now, we have these little things in our inner ear called semicircular canals - three small, fluid-filled tubes that help us keep our balance.

When our head moves, the liquid inside the semicircular canals sloshes around and moves the tiny hairs that line each canal. These hairs translate the movement of the liquid into nerve messages that are sent to our brains.

This helps your brain assess where you are in space and how fast or slow you are moving. Your brain then can tell your body how to compensate for shifts relative to gravity and stay balanced.

So here's why I found this so interesting:

The vestibular system can activate and amplify neuroplasticity - the incredible feature of our nervous system that allows it to change in response to experience.

In other words:

When your balance is challenged, you are triggering an optimum state of neuroplasticity.

😱

I know! The body is incredible.

If we want to achieve long-term change in our brains (i.e. access state of neuroplasticity), we need to pay deliberate attention.

Now, our vestibular system plays a big role in our attention and focus.

Unsurprisingly, when we're feeling off balance, we will naturally be more alert and focused. Think about when you're doing a handstand, or simply standing on one leg. This is because of the extra vestibular input our brain is receiving from the movement.

Compare that with spending the entire day seated (zero challenge to your balance) - you are more likely to feel a bit more sluggish.

The sensation of falling or being close to falling will release these neurochemicals that signal to your brain that something is wrong and needs to be adjusted. This creates the necessary chemical environment for neuroplasticity.

But it gets even more interesting:

The more novel the behavior is in terms of relation to gravity, the more it will open up the opportunity for neuroplasticity.

So if you’re very comfortable doing a handstand, you’ll get less plasticity because the errors and the relationship to gravity are very typical for you.

So the key takeaway:

Do exercises and activities that feel completely new to you, where you're feeling out of balance (without placing yourself at risk of course), to open up an optimal state of neuroplasticity.

Now to close the loop on my dizziness. You'll be relieved to hear it's gone away. I’m pretty sure I had a case of BPPV, which basically means ear crystals have drifted into one of my semicircular balance canals and are confusing my brain. Seems like it's a common thing and you can easily move the ear crystals back into place by doing a series of head movements while lying on the bed.

🎻 ADVICE FROM A WORLD-CLASS MUSICIAN

I’m intrigued by people who spent years and years obsessively perfecting a skill. They pick one thing and decide to become the best in the world at it.

In the newsletter The Process, Teddy Miltrosilis breaks down the five key principles of world-class musician Itzhak Perlman.

Each of his 5 principles can be linked back to the science of learning and neuroplasticity.

#1 Practice slowly

“If you learn something slowly, you forget it slowly.”

The brain needs time to absorb.

#2 Practice accurately

Research shows that the proper ratio for optimal learning is 85% success vs 15% errors.

When the task is too easy (i.e. 100% success), your nervous system is not learning from trial and error feedback.

When the task is too difficult (i.e. 100% errors), you’ll lose motivation and quit.

#3 Practice purposefully

Start by identifying a kit of reasons as to WHY you want to learn and change.

What is it you want to accomplish?

What is driving you?

Remind yourself of this why to release epinephrine in your system and increase your level of alertness.

These drivers can be positive, but negative motivators are just as effective. Epinephrine is a chemical so it doesn’t distinguish between positive or negative drivers.

#4 Practice in small increments

The adult nervous system is capable of engaging in a huge amount of plasticity but you need to do it in smaller increments per learning episode.

Key is to focus on smaller bouts of focused learning for smaller bits of information.

Follow your natural ultradian cycles of 90 minutes.

#5 Practice enough (but not too much)

Solid research shows that 90 minutes is about the longest period you can expect to maintain intense focus and effort toward learning.

Take regular breaks, and get enough sleep.

The actual rewiring and reconfiguration of our neural circuits happen during sleep and non-sleep-deep rest.

Thanks for reading!

Reply